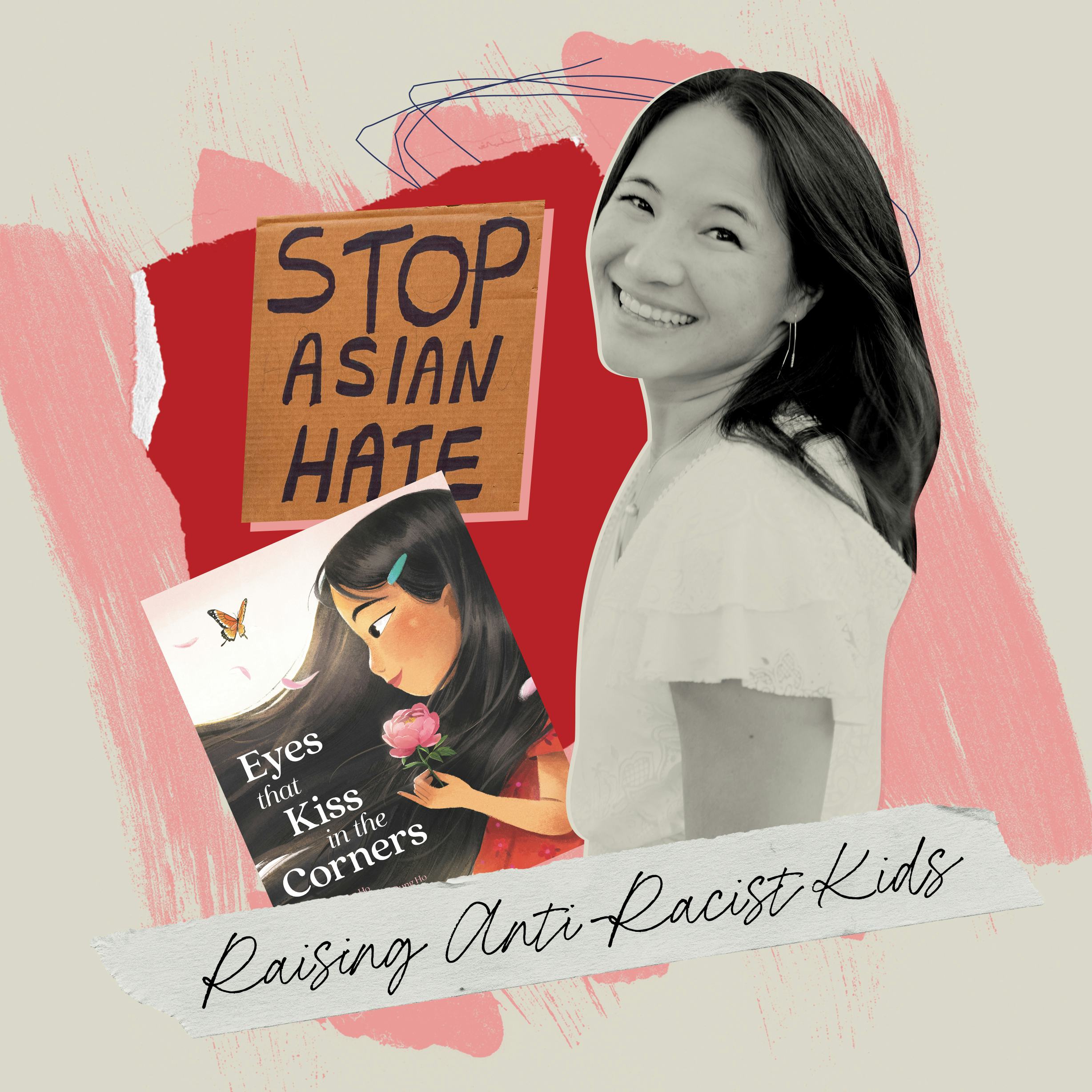

“Mama’s eyes that kiss in the corners and glow like warm tea crinkle into crescent moons when she comes home from work.” In Joanna Ho’s new children’s book, Eyes That Kiss In The Corners, a little girl finds delight, love, and pride in tracing her eyes from her mother’s and her grandmother’s. Told from the innocence of a child with wonderment and happiness, this story is for every little kid who wants to belong. It’s also a story — and a message — that couldn’t be more urgent.

Anti-Asian racism has long been a deep issue for this country. Tuesday, eight people were killed in a mass shooting; six of them were women of Asian descent. This comes on the heels of an uptick in documented hate crimes against members of the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities — the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, for instance, reports a 150% increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in 2020 (it also bears noting that these crimes are often underreported). We’re seeing a public reckoning. And we know that racism doesn’t begin and end with violence — there is incredible power in words and actions, like calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” or “Kung flu,” creating an environment that condones and encourages discrimination against Asians. This column, Raising Antiracist Kids, is not just centered around anti-Black racism. Indeed, as Ho pointed out when we spoke, anti-Black racism and anti-Asian racism are both tools of white supremacy.

Ho’s writing for children is light but engaging — and profoundly necessary as parents seek books that are fun to read to our kids while also introducing heroes with a variety of identities, in ways that are easy to grasp. I had the honor of talking with Ho, herself a mother of two, about her New York Times bestseller and what parents can do to make a change.

Below, you will also find actionable steps that parents can do in the here and now to work towards a world of equity for all.

Tabitha St. Bernard-Jacobs: As a Black mom of biracial kids, I've had to talk to my kids from as young as age 2 about race and racism. Can you share about your conversations with your kids about anti-Asian discrimination? How early did you have them? How are you talking to your kids about this?

Joanna Ho: My kids are 6 and 3 and I have been talking to them about race since they were born! We can't “kind” or “empathy” our way out of systemic racism. We need to give our kids the tools to speak about the social and historical reality — they experience it even if they don't know how to express it. Talking about it gives them language. Once they have the language, they learn to be critically conscious in the ways they absorb and navigate the world.

I need to help them create their own counter-narrative in which they are powerful, beautiful, worthy and valuable.

I try to talk about anti-Asian racism in a broader context so they know this kind of discrimination, like anti-Black racism and other forms of injustice and oppression, are all part of the systems of white supremacy. The world bombards them with these messages, so I feel a keen sense of urgency to combat and disrupt that dominant narrative. I need to help them create their own counter-narrative in which they are powerful, beautiful, worthy and valuable.

As a former English teacher and a children's book author, it's probably not a surprise that I believe children's books are an excellent tool of sparking dialogue and learning about race, racism and inequity. I bring them to protests — my 3-year-old came with me to a recent vigil against anti-Asian racism — and sometimes, my kids play games with their stuffed animals in which they march around the house chanting, "Black Lives Matter! Mni Wiconi!" Moments like that tell me these conversations and actions make an impact.

From your perspective, what is missing from the dialogue about the recent increase in anti-Asian racist violence?

Though the recent dialogue about anti-Asian racism isn't new, just as anti-Asian racism and violence are not new, it’s more public and seems to be engaging many — both in and out of the Asian community — who may not have been aware of or spoken publicly about [these] issues before. As such, it feels too early to assess what's missing from the dialogue because the more public version of this dialogue feels so nascent. There is a lot to explore and understand because Asians have been invisible for so long that too many people are painfully unaware of centuries of Asian history in America.

Some topics I hope continue to be explored include: how Asians can expand the Black/white binary of most racial discourse, racial solidarity against white supremacy, dynamics within an Asian American community that is not only diverse but also carries histories of colonization and imperialism that can hinder intra-racial solidarity, Asian complicity in our own oppression, Asians as the multipurpose tool of white supremacy (our position in the narrative changes to suit the needs of those in power and to oppress other marginalized communities), anti-Asian ignorance and sentiments in other marginalized communities, and the growing empowerment of an Asian community that will no longer be silent.

Being Asian isn't a monolith. There are many identities within that umbrella. Can you talk about this from the perspective of a parent?

I am the daughter of a Taiwanese and a Chinese immigrant, and the difference matters to me. My children are biracial —Chinese and white — and they are light-haired. I make a strong effort to nurture their Asian identity development because I know they will get plenty of messages of white normality from the world. I hope they grow up feeling a strong connection to their Asian heritage and a pride in who they are and where they come from. Though my Mandarin isn't amazing, I make an effort to speak to them in Mandarin. They went to a bilingual Mandarin preschool, and my son attends a local public Mandarin immersion elementary program. It's incredible for me to see them learning Mandarin and celebrating Chinese culture as part of their school experience — I had to attend Chinese school on Friday nights as a child and I didn't experience my culture or history as something important enough to learn about or celebrate in school.

I dream of a day when we can stop calling books ‘diverse,’ when we can stop using terms like ‘ethnic studies,’ when we don't need things like ‘Asian American Pacific Islander History Month’ because despite the good intentions, these are still othering terms. They still say white is core and everything else is other.

Why is it important for Asian kids to see themselves in Eyes That Kiss At The Corners, and also for non-Asian kids to learn from books like this one?

I think any book with positive and empowering representation of communities that have historically been marginalized is important and valuable. There are simply not enough books like these yet. I dream of a day when we can stop calling books "diverse," when we can stop using terms like "ethnic studies," when we don't need things like "Asian American Pacific Islander History Month" because despite the good intentions, these are still othering terms. They still say white is core and everything else is other.

I hope when Asian kids read Eyes that Kiss in the Corners, they grow up knowing they are beautiful because of the special characteristics they have. I hope they see their eyes not only for their physical beauty, but also because they are a representation of all that has been passed down to us and all that we will pass on to future generations. They are love and family and history and culture and power. I think it's important for Asian kids to see that their stories matter; this allows them to embrace their own power in the world. It's important for non-Asian kids to see these stories for the same reasons: to see that Asian stories matter, to challenge the dominant narratives about Asians, to dismantle racist beliefs and practices and systems that have existed for too long.

Wouldn't it be amazing if young people read this book and stopped making fun of Asians for our eyes? If an entire generation of Asian kids could grow up never going through this experience?

What do you wish parents of non-Asian children taught their kids about anti-Asian racism?

Wouldn't it be amazing if young people read this book and stopped making fun of Asians for our eyes? If an entire generation of Asian kids could grow up never going through this experience?

I wish parents of Asian and non-Asian children taught their kids:

Asian history in America. Anti-Asian racism didn't start with COVID. It didn't start with the Chinese Exclusion Act. It has a long, ugly history. But more than that, I want people to teach their kids about the achievements, contributions, joys, and complexity of the diverse Asian community.

Racism doesn't look the same for every community. This doesn't make anti-Asian racism less real. Ultimately, all forms of racism only serve to uphold our current inequitable systems of power and privilege.

Solidarity means speaking up, speaking out and taking action.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

#OneAction To Take Today:

Joanna shared some of her favorite books for kids. Head to your local indie bookstore or library and welcome these to your home.

It Began with a Page by Kyo Maclear

Drawn Together by Minh Lê and illustrated by Dan Santat

A Different Pond by Bao Phi and illustrated by Thi Bui

The Best We Could Do by Thi Bui

Raising Anti-Racist Kids is a column written by Tabitha St. Bernard-Jacobs focused on education and actionable steps for parents who are committed to raising anti-racist children and cultivating homes rooted in liberation for Black people. To reach Tabitha, email hello@romper.com or follow her on Instagram.

0 comments:

Post a Comment