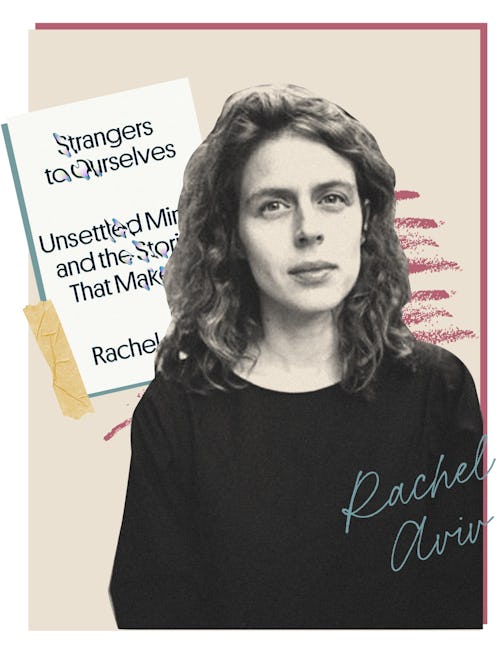

Rachel Aviv learned how to read on the eating disorders ward. At the age of 6, she was the youngest person on record to be hospitalized for anorexia. As an adult, Aviv has spent her career constructing incisive and empathetic portraits of individuals in psychological, medical, and social crises for The New Yorker. Her new book, Strangers to Ourselves: Unsettled Minds and the Stories that Make Us, is an expansion of this work. Through journal entries, published writings, and interviews with her subjects, and their families and doctors, Aviv investigates the ways inherited and imposed narratives of illness can impact healing. Strangers to Ourselves is also a sort of consummation of Aviv’s personal and professional journeys: The first person she profiles in the book is 6-year-old Rachel. “I don’t feel like it’s about me,” Aviv told me. “It’s about this very specific, discrete episode that shaped the questions I’ve been asking throughout the last 15 years.”

I have known Rachel Aviv for decades, and have been lucky enough to witness her sharp curiosity through our friendship and her warm sensitivity as a parent of two young kids. As a person with my own genetic inheritance of mental illness, reading this book was both intellectually invigorating and cathartic: Each story offers carefully rendered scenarios that resonate emotionally but defy easy answers. Aviv is more interested in exploring the edges of illness and identity than defining them, a rare calling in a world that prefers a concise TL;DR. We spoke from her home in Brooklyn, where she’d just recently set up her own dedicated workspace.

I know this book is not a parenting manual by any means, but I was inevitably collecting do’s and don’ts as I read. The lives of the individuals you write about — including your own — were shaped in many ways by family relationships. You dedicated the book to your parents. You make reference to avoiding the “career” of mental illness after you were hospitalized. In retrospect, do you think there were ways in which your parents helped you do that?

I think that my family — and my school too — was not judgmental. At school, the teachers not only didn’t draw attention to aberrant behavior (like my refusal to sit down in a chair), but they also allowed it. I think that was really helpful. Judgment can often push people away from their families or their communities into spaces that isolate them and maybe exacerbate a mental illness.

It’s interesting you mention a non-judgmental perspective, because one thing that I think really sets your work apart is your total lack of judgment toward the people you write about — in this book and in your pieces for The New Yorker.

In general, when it comes to people doing things that defy social expectations, my instinct is to relate. I can see how, if a few things had gone differently in my life, I would have done the same thing. I have a sense of just how arbitrary it is that anyone gets to stand on firm footing, and how easily that firm footing can dissolve.

Each one of the stories in the book, not just yours, is prismatic — you have the perspective of the individual you’re profiling, but also of the family around this individual. And in some cases, a large portion of the chapter is from another perspective, like Bapu — a Tamil woman in India who is pulled from her path as a mystic by a diagnosis of schizophrenia — whose story is told in part from her daughter’s perspective. To me, this approach is one reason why the book lets us into such an empathetic and holistic view of these events. Can you talk about how you arrived at writing the book this way?

It usually began with one person’s perspective, but then there would be these moments… When I went to India, the first person I met was Karthik, Bhargavi’s brother and it was amazing to see how differently he framed his mother’s illness. I love that moment where you’re like, “Oh, I’m actually seeing this through a completely different lens.” Especially with Bapu, there was this very slippery sense that no one could quite find the right framework for what she was going through. And her two children had been completely affected by it. Her children’s different interpretations had given their lives meaning in a way — they pursued work related to those interpretations. I had the same experience with Naomi: I would interview her, but then I would interview her sister, who had a very different perspective. In writing, I wanted to preserve that sense of total shift. It can be seen from one perspective or another, and I don’t actually have to choose.

Also, I quickly realized that they were not just individual stories. They were family stories, and they spanned a few generations. Each family member and each generation had such a different way of making sense of it. I was trying to reflect the experience of moving from one conversation to the next — you leave and for a few hours, you’re like, “That’s the truth.” I hoped to recapture that experience, so that a reader can feel like when they’re in someone’s head they have the correct interpretation, but when they leave that space, they are free to adopt someone else’s view, too.

The family dynamics you trace in these stories are so powerful. Bapu longs to be with her children and they want to be with her, but her illness and their family’s cultural beliefs keep them apart. Ray, a man who suffers a breakdown after his kids moved away and is institutionalized multiple times, spends his whole life mourning the fact that he can’t be an active father. But when he finally earns his son’s forgiveness, he’s unable to be present with him. Heartbreak after heartbreak.

Someone asked me why there was so much about the relationship between parents and children in the book. That’s one of the main struggles in life, and so, of course, I gravitate towards that. I do think I’m more attentive, and I probably ask better questions about those sorts of things than I did seven years ago, before I had a child. There’s one story I wrote that I think I would have approached differently if I had been a parent: a story about a mother who had left her 3-year-old son in her crib and then Child Protective Services took him away. I didn’t fully appreciate what it meant to be a single mother, how hard and lonely it can be. I went really quickly from “she’s overwhelmed” to “she left her kid in the crib.” I feel like there was an entire world happening in her mind to get from point A to point B, and I would have liked to have dwelled in that space a lot more.

Well, it’s not the same story, but you got to the heart of a similar impossible difficulty in the chapter about Naomi — a Black single mom who ends up losing one of her sons after she jumps into a river, believing she’s escaping people who mean to murder her family.

Yeah, I was able to imagine that mental space a little bit better, so I could ask better questions.

These are also cultural stories you’re telling. And today we’re living in a culture in the United States that is so stressful that a government-convened panel recommends everyone under 65 get screened for anxiety. In the book, you refer to Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia a number of times — a text from the early 20th century where Freud sets up a diagnostic dichotomy between an appropriate response to something terrible (mourning) and an inappropriate response (melancholia). I wonder if that’s still a useful way of dividing our experiences today.

It is still a good dichotomy, but the terrible things keep mounting. An appropriate response to the things going on in the world is actually very extreme. Perhaps it seems like “healthy” people are actually having disproportionately small responses to it.

But litigating whether it’s proportional or not doesn’t take away from the fact that people might want medications to make life more tolerable and bearable. I guess one way to think about it is, “Is your sense of despair getting in the way of doing the things you want to do with your life — family-wise, work-wise?” And if it is, then maybe treatment or medicalizing can be an appropriate response.

More of a functional definition of “appropriate,” then. There are no easy takeaways in this book. You have almost an asymptotic relationship to conclusions throughout the stories — your stories approach closure but never quite arrive there. What do you hope for your audience as they read?

I wanted people to have an experience of making connections, maybe doubting some preexisting beliefs, changing the way they thought about people — maybe feeling less alone in certain thoughts. I wanted to impart an experience more than like a set of ideas.

I certainly felt that way. I do think that one of the hardest truths in life — parenting, family, anything big — is that you won’t have full resolution. Resolution is a pretty evasive concept.

Even recovery is in flux. A story that ends with someone’s recovery from mental illness is a resolution for that moment. It’s working now under certain circumstances, because you’re a certain age and you’re surrounded by certain people, but we don’t know if it will work forever.

To that point, you end the chapter on your childhood anorexia almost as a success story — you go on to have a healthy life. And then toward the end of the book, you discuss your own experience with Lexapro for anxiety, which I take as well. That makes the narrative a little bit more complicated. Was it scary to write about what was happening for you in the present?

In order to write about it, I wasn’t like, “Oh, I’m going to catch the reader up with myself today.” It was more that I was really troubled by this thing that felt like a cultural phenomenon — why were we all taking the same medication? I tried to avoid the feeling of vulnerability by thinking of the writing as a concrete way of opening up into a larger story.

I’m still taking Lexapro even though I’ve thought about trying to stop. Has anything changed in your relationship with the medication since you wrote the book?

At some point while I was writing, I was still trying to go off slowly. And then I was like, whatever, that’s not the end goal. As I watched my kids get older, I also had a greater appreciation for genetics— seeing certain characteristics move from one generation to the next, and knowing how you can look at an older family member and think that they tried their best, but could have been better in a lot of ways. That gave me more permission to keep taking a medication that I don’t know that I strictly need, for medical reasons. I can focus on maintaining a version of myself that feels like it’s doing better as it moves through the world.

0 comments:

Post a Comment