Last fall I was sitting in my therapist’s office, crying about whether I would ever have kids. In my 20s, it had been so easy to swear I would never be this woman: obsessed with fertility, reducing her life and body to a steadily-ticking time bomb. But nothing humbles you like the passage of time, and there I was, 36 and single and crying. “Have you thought about freezing your eggs?” my therapist asked.

I’d encountered the question before, of course. I knew other women who’d done it, who said it had changed their lives. Taken a weight off of their minds. Allowed them to finally relax, date for fun, and not worry so much.

But I had always been resistant. There was the expense, first of all: usually in the neighborhood of $10,000, unthinkable on my freelancer’s income. But more than that, I didn’t want to have to admit to anyone — especially myself — that it was time to do anything other than wait and see. Having to freeze my eggs felt like a series of compounding failures: failure to be eternally young, to be wanted and loved, and, on top of that, to be like, totally chill about it all.

The reason I go to therapy is so that someone will look me in the eye and say: you sound really stupid right now, Zan.

I was forced to admit that I did. So I asked my parents to cover the costs of a round, and they agreed. (They can afford it, and would very much like a grandchild.) From there, it felt like fate took over: I mentioned the idea to a friend who went to medical school, and she lit up. Her favorite classmate had just started working at a fertility clinic and was looking for clients; she put us in touch. Dr. A assured me that actually, 36 was the perfect time to be doing this: old enough that the eggs we got were likely to be useful to me, but young enough that their quality would still be good.

I was buoyed by a sense that everything was falling into place; that I was on the path, as we say out here in LA. That even though this wasn’t exactly what I had wanted, it was at least going to be easy. I would endure a couple of uncomfortable weeks, learn how to give myself shots, watch my ovaries swell to the size of tennis balls, and then I would be done. I already looked forward to how I’d feel after: triumphant. Accomplished. And of course, that most sought-after state of all: relaxed.

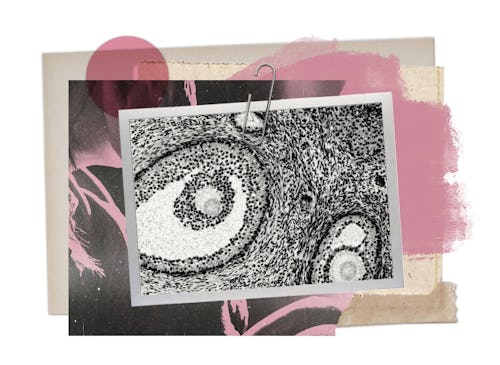

I went in for an initial scan — a brief blood draw, a transvaginal ultrasound. A few days later, I got my results.

And that was where the fairytale ended. It turned out that my ovarian reserve was low — basically, I just don’t have that many eggs left. (I will never get over how uncanny it feels to talk about “my eggs.”) If I was trying to get pregnant the old-fashioned way, it wouldn’t necessarily matter — after all, for that, you only need one. But egg freezing is a numbers game. You want to harvest as many as you can at once.

I knew how devastating fertility struggles could be in theory. My friend Doree Shafrir made a whole podcast about the subject. But as I cried my way through the next few days— I am a champion crier — I realized that I had miscategorized this adventure in my head. I had not thought of egg freezing as a fertility treatment. In fact, I had unconsciously considered it as a shortcut away from the very situation I now found myself in. An insurance policy against fertility issues; a promise that I could simply buy my way out of running out of time.

I know I am not alone, and how could I be? The industry has a vested interest in maintaining this delusion. Business Insider recently wrote about how clinics are targeting increasingly younger women with the promise of a “set it and forget it” approach to having kids: the alluring notion that fertility is a problem that, thanks to modern medicine, can be easily solved.

But there are warnings, if you look for them. As I tried to figure out how many rounds I’d have to go through to get a reasonable number of eggs, I landed on a New York Times headline that read, “‘Sobering’ Study Shows Challenges of Egg Freezing,” which assured me that my low egg count could be a big, big problem. It turned out that it had been shortsighted at best not to do more research before plunking down some $12,000 of my parents’ money on something that might never yield meaningful results. Because if I wanted any real assurance of a baby someday, I’d have to do this — and spend that much — somewhere between two and five more times.

The length of that initial cycle, from first bloodwork to the final retrieval, was 12 long days, and I spent them swimming in confusion and grief. I had just convinced myself to try, only to be reminded, in no uncertain terms, that all of my effort might be in vain. I now felt not only old and unwanted but also stupid and wasteful.

Fertility presses on so many tender spots: it thumbs hard at bruises around what the “right” kind of body is, and whether you have one, and whether you could be doing more to achieve one.

When I had talked to friends before the procedure, we had all framed the decision to freeze eggs as sort of like getting LASIK, which I also did a few years ago. A little risky, yes, but ultimately common and barely noteworthy. I had not taken the possibility of failure, or even grief, into account.

And it's true that, even if someone had tried to tell me how wrong I was, I’m not sure I would have been willing to hear it. On some level I knew instinctively that once I stopped being casual about this, I would have to look at a tangle of complications I rarely want to acknowledge, let alone confront. The reminders that fertility, pregnancy, birth — they’re medical, yes, but they’re also something more.

Fertility presses on so many tender spots: it thumbs hard at bruises around what the “right” kind of body is, and whether you have one, and whether you could be doing more to achieve one. But more than that, it reminds us that for all of the signs of aging that we can forestall or hide — gray hair, wrinkled foreheads — we cannot stop the clock entirely. That there are certain things that you cannot hold onto forever. That one of them is, inevitably, your own life.

That sounds dramatic. But I just mean: my body has changed and evolved in so many ways in the last 37 years. There are yoga postures, for instance, that used to be as natural as breathing that, at some point, I lost my grip on. The difference is, if I really applied myself, I could probably get my flying crow back. But there is no amount of effort and training, or medical intervention — whether it be supplements or acupuncture or prayers or even egg-freezing— that will make my body have a baby it doesn’t want to have. If I haven’t already lost my fertility, someday I will. As surely as I will someday lose my breath.

Put another way: Since I got my first period at 10, I have had to grapple with the idea that my body had the potential to create life. How could losing that not feel like a kind of death?

You can see why having to pay $12,000 to figure all of that out really felt like adding insult to injury.

In the end, after those harrowing 12 days, my first cycle went well. The retrieval was smooth, and we got five mature eggs, which put my chances of having a kid from them at an estimated 36%.

And then, knowing everything I (now) knew, I decided to do it again.

This time, I paid for the cycle myself, with the help of a very good year at work and the Jewish Free Loan Agency, which made the money aspect of the procedure much easier to swallow. I got the exact same number on try #2 as try #1, which means I now have approximately a 50/50 chance of getting a child from those eggs. The flip of a coin. Somehow, that feels exactly right to me. It sits on the knife’s edge of possibility: a hope, but not a certainty. A door I’ve opened and may or may not ever be able to walk through.

I think of it like an ante, a way of putting skin in whatever game I’m playing with the universe. Saying, I want this very badly, and I’m willing to sacrifice something for it.

The egg freezing process is a lonely one, or at least it was for me. I got bloated and tired, but more than that I felt vulnerable, constantly aware of my swollen ovaries, of the promise and potential they held. Both times I burrowed down, spent the days mostly alone, witnessing my body as it took syringes of chemical intrusion and transformed them into — well, we’ll see what, eventually. It gave me a lot of time to think. And what I thought a lot, that second time, was: why am I doing this again?

It also gave me time to think through an answer. I have so little control in this situation. I can’t magically conjure a boyfriend or husband, without whom having a child is, for me, financially and logistically infeasible.

But time does continue to pass; my body continues to change. Freezing my eggs might help less than I want it to. But it has to be better than doing nothing. At the very least, I think of it like an ante, a way of putting skin in whatever game I’m playing with the universe. Saying, I want this very badly, and I’m willing to sacrifice something for it.

Trying is a loaded word around fertility — and what does it mean, to try to make a body do something? Biology is one of the more stubborn facts I’ve encountered in my lifetime. But also, this is something I want, and I probably have a few more years left yet. What is there to do but open up my palms, surrender to chance, and ask for help? Why wouldn’t I try whatever I can?

Alexandra Romanoff is the author of Big Fan, the debut romance novel from 831 Stories. She is also a journalist, a cultural critic, and the author of three previous novels. She also co-hosts the podcast On the Bleachers, which examines the intersection of sports and pop culture. Her favorite member of One Direction is Louis Tomlinson. She lives and writes in LA.

0 comments:

Post a Comment