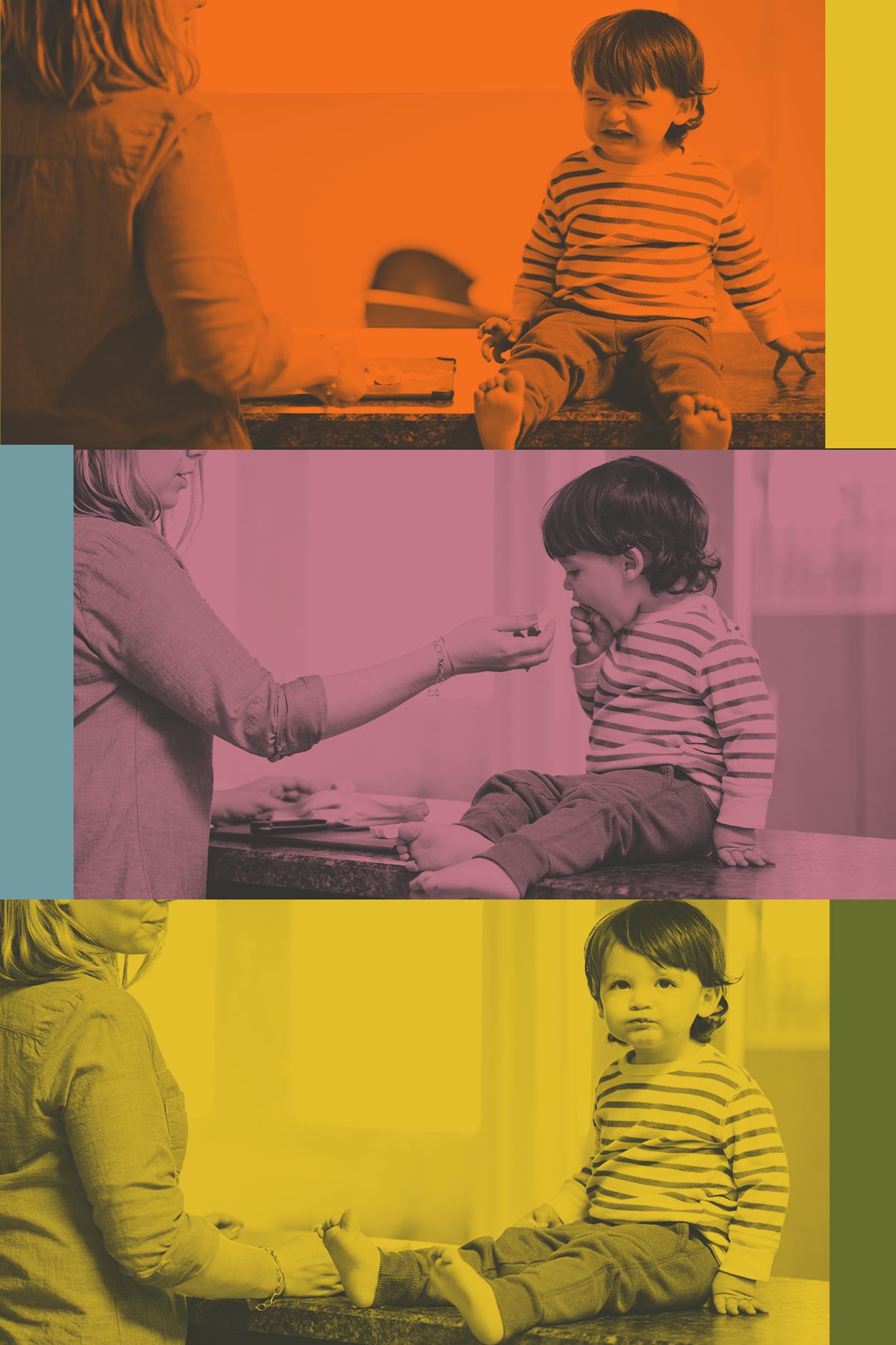

Six months into the pandemic, with school closed and social outings canceled, my 5-year-old son was getting every single meal from our kitchen and he was eating fewer foods than ever. Gone were the restaurant outings where a tempura-battered broccoli floret might present a deep-fried gateway to eating plants. Gone were the visits from the public health department to his Title I school, where an AmeriCorps do-gooder pushed an A/V cart loaded with fresh produce into his classroom and issued stickers to kids who would try, for example, a beet. “I tried it!” the sticker read. (He always came home with a sticker on those days, though once he confessed that after eating the beet, he gagged so hard that he threw up.)

I had long been a disciple of what registered dietitian and licensed social worker Ellyn Satter calls the “division of responsibility” when it comes to feeding children. In Satter’s model, the parent is responsible for choosing and preparing the food for the child, and the child is responsible for eating the amount that they need. No pleading, no cajoling, no bribery, no drama. As a new parent and lifelong slacker, the idea that it was not on me to hoodwink my selective then-toddler into eating a variety of foods was intoxicating to me. I simply had to continue to serve him small portions of foods I knew he would never touch, dump his entire plate into the compost bin after meals, and convince myself I was playing the long game. I was both the con and the mark here, and for years I coasted on this, convinced that I was doing my best. I mean, the word “responsibility” was right there in the name.

Testimonials on Satter’s site described children at age 7 suddenly ravenous for a varied, nutritious diet as if they’d been resuscitated from a years-long nutritional coma. I wanted so badly to believe in this witchery that I managed to disable the roaring skepticism machinery that typically prevents me from buying into any belief system, from parenting gurus to organized religion to political parties. But I was broken by the relentlessness of modern parenthood, the disappointment of my dashed expectations. In other words, I really needed this to work out.

I didn’t think about human babies at all for most of my life. They were hairless, sticky, and they were always staring at me. But when I was 28, seemingly out of nowhere, babies invaded my vision like they were an ad I once clicked that was algorithmically chasing me through the tabs of my life.

I didn’t have a fantasy of motherhood before I pursued it. Some people dream of sharing a certain book series or teaching their child their sport. I didn’t think about human babies at all for most of my life. They were hairless, sticky, and they were always staring at me. But when I was 28, seemingly out of nowhere, babies invaded my vision like they were an ad I once clicked that was algorithmically chasing me through the tabs of my life. I had to have one. There was no clear vision of what this would look like for me, but I did have one pillar of certainty: any child of mine would be an adventurous, enthusiastic eater. They would be an adventurous, enthusiastic eater like me.

You know what comes next: the universe issued me a child custom-built to subvert my ego.

When it came to food, my son was unimpressed. As an infant, he was bored by the twee solids we prepared. The steak-frites of roasted squash and the fingers of avocado dusted with sesame seeds (for grip!) were flung to the floor. He used his tongue to eject purees down his chin. If he ate any of his first birthday cake, it was a cursory lick of the frosting. He was much more interested in hamming for the grandparent press corps pointing their phones at him in his paper hat. Who needs to eat when you can perform? Despite this, he was growing well. Like a countertop sourdough, he seemed to double in size nightly despite ingesting mostly air. His doctors coached us to continue offering a variety of foods and not to sweat it. I sweated it. Around this time, a friend proudly shared a time-lapse video on Instagram of her same-age toddler housing an adult-sized dinner portion of sushi. I watched it over and over like it was the moon landing. It didn’t seem possible but there he was, jawing the sh*t out of a tuna roll.

I envisioned my son moving into his first college dorm room, unrolling blacklight posters and explaining to his new roommate, “Oh, this is my insulated lunchbox of 4 oz. bottles of milk. Yeah, I never really got into food. But it’s totally fine if you eat in the room. Most of my friends back home eat, too.” It was Ellyn Satter and her principles that saved me from this self-imposed gyre of feeding-based torture. I kept to the orthodoxy and replaced my anticipatory visions of the future. Instead of picturing my boy at a rowdy house party pulling from a flask of milk, I envisioned the same boy ordering something fussy, possibly vegan, while out to dinner with me 15 years in the future. In this fantasy, I toss my white Emmylou-style shock of hair back and remind him of the gagging on beets in pre-K thing. Oh, how we laugh and laugh.

My delusions afforded me several years of peace during an otherwise turbulent time. We moved three times, including out of state, welcomed another baby, and then, of course, March 2020 arrived on thundering hoofbeats of sh*t. My husband, for his part, supported the feeding principles but had his concerns. He had been a picky eater in childhood and worried we might miss some critical window to spare our child the pain he experienced. Our son was now entering kindergarten and approaching the developmental point at which I was told he might spring forth a different kind of eater. Instead of his world widening with new experiences, it was on a tight taper. He was now pushing back if sandwiches were not cut a certain way (four triangles), or if cheese was not an acceptable color. I knew this type of power play was developmentally appropriate but taken with the ever-vanishing list of acceptable foods, it was simply too much. It was then that I committed an act of sedition.

I Googled “ellyn satter evidence based?” I saw what I needed to see. Then I Googled “pediatric dietitian near me.”

I watched as my own face on the screen, airbrushed by Zoom’s “touch up my appearance function,” experienced ego death.

My feelings going into the dietician consult, conducted via teleconference, were twin surges of excitement and dread. I was eager to try a new approach, something tailored to my individual child. But I was certain the way forward would come with homework for me and my husband, sneaking lentils into muffins and buying special vegetable punch-cutters in fun shapes like I’d seen on the kid nutrition Instagram accounts I followed. What I came to understand quickly was that this was not a conversation where I would walk away with tricks to perform nutritional sleight of hand. I did get some practical course correction (he needed a more filling after-school snack so that he didn’t come to the dinner table starving and fragile), but mostly I got my head shrunk.

“If your son’s diet couldn’t be changed for the rest of his life, if he had to move through a world hostile to this kind of eating behavior indefinitely, how would you want him to think back on his childhood?" she asked me. "Would you want him to think of it as a place of safety or a place of shame and disappointment?” I watched as my own face on the screen, airbrushed by Zoom’s “touch up my appearance function,” experienced ego death. A tendency toward selective eating often has a genetic component. My husband and son share many qualities: a cheerful disposition, a wicked recalcitrance. There is a photo of my husband as a child with his head on the table next to his dinner plate, sleeping. He was told he had to stay at the table until he tried the meal. He wouldn’t try the meal. The image has always been funny to me, my husband’s essential obstinance captured on film so early in his life. But there is also a sadness to it. It is exhausting to be a parent in charge of dinner every night, and it is exhausting to be a kid pressured to eat something “scary.”

When my son was a toddler, I needed an authority to give me an orthodoxy to which I could cling. Now, I needed an authority to give me permission to be the authority of our own family.

When I feel my patience with my son wearing thin, I call to mind a vivid memory I have from childhood, of being dared to eat an earthworm — the way revulsion and dread seized me as I lowered it, still wriggling, onto my tongue. Maybe this is the same sort of dread my son feels when he's served certain foods and we watch him, insisting he doesn't have to eat it. Maybe it's not the same at all, but in the moment, it helps me muster compassion.

When my son was a toddler, I needed an authority to give me an orthodoxy to which I could cling. Now, I needed an authority to give me permission to be the authority of our own family. These days, my son takes the exact same packed lunch to school every day, and dinnertime is as peaceful as it can be with two young children. My son picks what he would like from what is offered and if he makes a reasonable request for something different from the kitchen, we accommodate it. His toddler sister is an adventurous eater for now and we don’t hesitate to put any type of food right on her plate, even if she doesn’t end up tasting it. I often encourage her to try bites of things, a definite Satter no-no. She is a different child who requires different parenting.

It is seductive to think of our children as a canvas that we paint, instead of a painting that reveals itself to us over time if we’re still enough to pay attention. As for my hope for an expansive gastronomic life for my son, I no longer traffic in ideas about the adult he might be. It’s impossible to resist envisioning his future, but when I do now, I see these daydreams for what they are: visual hallucinations of my desires, anxieties, and hopes. And I keep my visions to myself.

0 comments:

Post a Comment