The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a grim report on Monday that showed more than 80% of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. between 2017 and 2019 were preventable. Among American Indian and Alaskan Native (AI/AN) people, that number was a staggering 93%.

Pregnancy-related deaths are defined by the CDC as a death while pregnant or within a year of pregnancy, regardless of cause. Among the 1,018 pregnancy-related deaths analyzed by the Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs), multidisciplinary committees that review pregnancy-associated deaths, 22% of deaths occurred during pregnancy, 25% occurred on the day of delivery or within seven days after, and more than half — 53% — occurred between seven days to one year after pregnancy.

Mental health conditions (including death by suicide and overdose) accounted for nearly a quarter (23%) of pregnancy-related deaths. This was followed by hemorrhage (14%); heart conditions (13%); infection (9%); thrombotic embolism (9%); cardiomyopathy (9%); and hypertension (7%), though leading underlying causes varied by race and ethnicity. For non-Hispanic Black people, for example, heart conditions were the leading underlying cause. For Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and AI/AN people, mental health conditions were most commonly to blame. Non-Hispanic Asian women were most likely to succumb to hemorrhage.

In a statement, Dr. Wanda Barfield, director of the CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health at the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion praised the report for providing a “much clearer picture” of this health crisis. “The report paints a much clearer picture of pregnancy-related deaths in this country,” Barfield said. “The majority of pregnancy-related deaths were preventable, highlighting the need for quality improvement initiatives in states, hospitals, and communities that ensure all people who are pregnant or postpartum get the right care at the right time.”

This information is the first to be released as part of the Enhancing Reviews and Surveillance to Eliminate Maternal Mortality (ERASE-MM), a CDC-funded program to support MMRCs reviewing pregnancy-associated deaths to get a more complete picture of the circumstances surrounding the tragedy. These multidisciplinary committees are organized at a state or local level and include representatives from a wide range of disciplines, including public health, obstetrics and gynecology, and maternal-fetal medicine as well as nursing, midwifery, forensic pathology, mental and behavioral health, patient advocacy groups. The CDC recently increased its investment in MMRCs in an effort to better understand and, more importantly, prevent pregnancy-associated deaths.

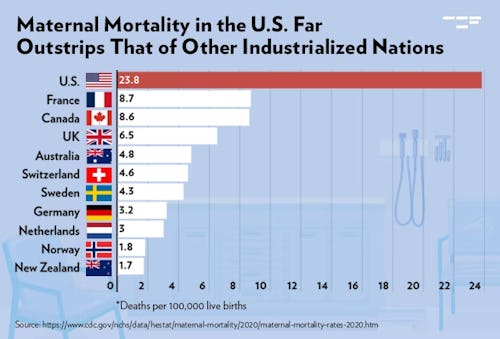

Among wealthy nations, the United States’ maternal mortality rate has exponentially outpaced those of our peers, and has disproportionately affected Black women, who are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. During the Covid-19 pandemic, which post-dates the data analyzed in this latest report, maternal mortality rose, from 23.8 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with a rate of 20.1 in 2019.

In June, the White House released its Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis. The plan comprises 50 actions for more than a dozen federal agencies based around five main pillars to address maternal death including increasing access to wider variety of maternal health services; empowering patients to make decisions in their own care; advancing data collection, standardization, transparency, and research; expanding and diversifying perinatal care providers; and strengthening social and economic supports for people before, during, and after pregnancy.

In a discussion with Morning Edition’s Public Health Review, Dr. Jamila Perritt, President and CEO of Physicians for Reproductive Health, has suggested that the plan could be an important tool in helping communities meaningfully take action in saving new parents’ lives, particularly in light of the fact that community care providers already recognize some ways to improve patient outcomes, particularly for BIPOC folks, but can often lack to resources to successfully implement these actions. “What we’re asking of the federal government and local health departments is not to create a brand new plan for how to get us out of this mess but instead to listen to the folks who have been working in community on the ground for decades to address this issue.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment